The Devastating Effects of Ocean Plastic on Marine Life

Of course. As an SEO expert, I will create a comprehensive, engaging, and unique article optimized for search engines and long-term relevance, following all your instructions.

Here is the article:

—

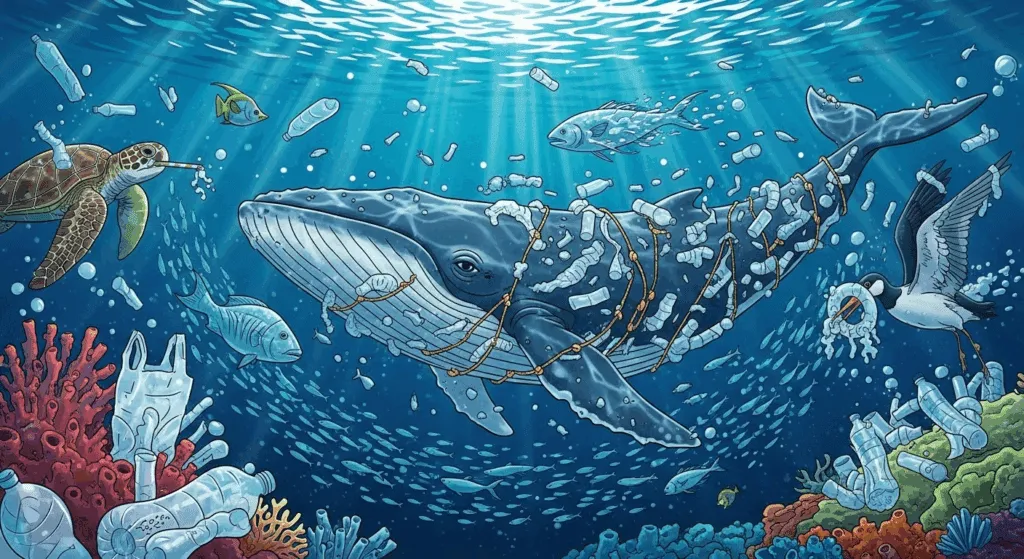

The vast, blue expanse of our oceans, a source of life, wonder, and sustenance, is choking. A silent and pervasive invasion of plastic debris is transforming these vibrant ecosystems into hazardous obstacle courses for the creatures that call them home. From the sunlit surface to the darkest abyssal plains, the evidence is undeniable and heartbreaking. Understanding the full spectrum of the effects of plastic pollution on marine life is not just an academic exercise; it is a critical step in confronting one of the most pressing environmental crises of our generation. This plague, born of human convenience, now threatens the very fabric of marine biodiversity, creating a ripple effect that ultimately reaches our own shores and dinner plates.

The Scope of Ocean Plastic Pollution: A Crisis Unfolding

Before delving into the specific impacts on wildlife, it's crucial to grasp the sheer scale of the problem. It is estimated that a staggering 8 to 14 million metric tons of plastic enter our oceans every single year. To visualize this, imagine a garbage truck's worth of plastic being dumped into the sea every minute of every day. This relentless influx is a result of inadequate waste management systems on land, industrial runoff, littered coastlines, and direct dumping from marine vessels. Once in the water, this plastic doesn't simply disappear; it embarks on a journey that can last for centuries.

The persistence of plastic is its most sinister quality. Unlike organic materials, it does not biodegrade. Instead, it breaks down into smaller and smaller pieces through photodegradation (exposure to sunlight) and physical abrasion. This process transforms large, visible items like bottles and bags into microplastics—fragments less than five millimeters in size—and eventually nanoplastics. These fragments are carried by ocean currents across vast distances, accumulating in massive rotating currents known as gyres. The most infamous of these is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a concentration of debris spanning an area more than twice the size of Texas.

This global distribution means that no corner of the ocean is safe. Plastic waste has been discovered in the most remote locations imaginable, from the pristine ice of the Arctic to the crushing depths of the Mariana Trench, the deepest point on Earth. It is a constant, physical, and chemical presence that marine organisms cannot escape. The crisis is not a future problem; it is a present and escalating reality, with the total volume of plastic in the oceans projected to outweigh all the fish by 2050 if current trends continue. This sets the stage for a cascade of devastating consequences for all forms of sea life.

Direct Physical Threats: Entanglement and Ingestion

The most visible and gut-wrenching effects of plastic pollution are the direct physical harms it inflicts upon marine animals. These threats primarily fall into two categories: entanglement in larger debris and ingestion of plastic pieces mistaken for food. Both can be acutely lethal, causing slow and painful deaths, and they affect a wide array of species, from the smallest invertebrates to the largest whales. These incidents are not rare; they are a daily occurrence in every ocean around the world.

Entanglement happens when an animal becomes trapped in plastic debris. Common culprits include discarded fishing nets (often called "ghost nets"), six-pack rings, plastic bags, and packing straps. Animals like sea turtles, seals, sea lions, dolphins, and whales are particularly vulnerable. They may swim into a floating net or get a ring stuck around their neck or flipper. The initial entanglement is just the beginning of a prolonged period of suffering that often leads to a tragic end.

Ingestion occurs when an animal consumes plastic, either intentionally by mistaking it for prey or unintentionally while feeding on other organisms. A sea turtle might mistake a floating plastic bag for a jellyfish, its primary food source. A seabird might scoop up brightly colored bottle caps, thinking they are fish or squid. Filter feeders like barnacles and mussels, which process large volumes of water, passively consume vast quantities of microplastics. This mistaken identity has severe and often fatal consequences for the animal's digestive system and overall health.

The Lethal Trap of Entanglement

Once an animal is entangled, it faces a multitude of life-threatening challenges. The plastic can act like a straitjacket, restricting movement and making it impossible to swim, hunt for food, or escape from predators. This leads to exhaustion, malnutrition, and increased vulnerability. For air-breathing animals like turtles and marine mammals, becoming entangled in heavy debris can prevent them from reaching the surface, resulting in drowning. A ghost net, for instance, can continue to "fish" for decades, indiscriminately trapping and killing countless animals.

The physical injuries caused by entanglement are horrific. As an animal grows, a constricting piece of plastic like a packing strap or ring will not expand with it, cutting deep into the flesh. These lacerations can cause severe infections, blood loss, and immense pain. In some cases, the entanglement can lead to amputation of a limb or flipper, severely compromising the animal's ability to survive in the wild. Even if an animal manages to survive, the chronic stress and injuries can weaken its immune system and reduce its reproductive success, impacting the entire population over time.

Ingestion: A Deceptive Meal

When an animal ingests plastic, it can cause immediate and catastrophic internal problems. Sharper pieces can puncture the stomach or intestinal lining, leading to internal bleeding and fatal infections. More commonly, the accumulation of plastic in the gut creates a physical blockage. This prevents the animal from properly digesting real food, creating a false sensation of being full. The tragic irony is that an animal can starve to death with a stomach full of plastic.

The consequences extend beyond simple blockages. The lack of proper nutrition weakens the animal, making it more susceptible to disease and predation. An albatross, for example, will fly thousands of miles to find food for its chick, only to return and regurgitate a deadly meal of plastic fragments. Scientists examining the stomach contents of deceased seabirds and whales regularly find a shocking collection of lighters, bottle caps, and plastic shards. This "junk food" diet offers zero nutritional value and serves only as a slow-acting poison, highlighting a direct and deadly link between our throwaway culture and the suffering of marine life.

The Invisible Danger: Microplastics and Their Chemical Impact

While larger pieces of plastic cause visible and brutal harm, the microscopic fragments present a more insidious and pervasive threat. Microplastics are the tiny, often invisible particles that result from the breakdown of larger items or are manufactured directly, such as the microbeads once common in cosmetics. These particles are now ubiquitous in marine environments, found in surface water, beach sand, and the bodies of more than 700 marine species. Their small size allows them to be ingested by a much wider range of organisms, starting at the very bottom of the food chain.

The danger of microplastics is twofold. First, they cause physical harm on a microscopic level, damaging cells and tissues. More alarmingly, they act as tiny sponges for toxic chemicals. Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) like DDT, PCBs, and other industrial chemicals are hydrophobic, meaning they repel water and are readily attracted to and absorbed by the surface of plastics. This means a single microplastic bead can become a concentrated dose of poison, thousands or even millions of times more toxic than the surrounding water.

When an organism ingests these toxic-laden plastics, the chemicals can leach out into its fatty tissues, a process known as bioaccumulation. As smaller organisms are eaten by larger ones, these toxins are passed up the food web and become increasingly concentrated at each trophic level. This process, called biomagnification, means that top predators like dolphins, sharks, seals, and polar bears end up with dangerously high levels of toxic chemicals in their bodies, with severe consequences for their health and survival.

Bioaccumulation and the Poisoned Food Web

The journey of a microplastic toxin through the food web is a clear illustration of ecosystem-wide contamination. It begins when a microscopic zooplankton ingests a tiny plastic fiber. That zooplankton is then eaten by a small fish. A larger fish, in turn, eats hundreds of these smaller fish, accumulating the toxins from all of them. Finally, a marine mammal like a dolphin or a seabird like a puffin consumes multiple larger fish, receiving a highly concentrated dose of the accumulated poisons.

For these top predators, the health effects are devastating. Scientific studies have linked high levels of plastic-associated toxins to a range of problems, including reproductive failure, a suppressed immune system, behavioral changes, and endocrine disruption. This means animals may be unable to produce viable offspring, become more susceptible to diseases they would normally fight off, and have their natural hormonal balances thrown into chaos. It is a slow, invisible poisoning that threatens the long-term viability of entire species.

The Leaching of Toxic Additives

Beyond the toxins they absorb from the environment, plastics themselves contain a cocktail of chemical additives used during the manufacturing process. Chemicals like bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and flame retardants are added to give plastics their desired properties, such as flexibility, color, or durability. These chemicals are not chemically bound to the plastic polymer and can leach out over time, especially as the plastic breaks down in the marine environment.

Many of these additives are known endocrine disruptors, meaning they interfere with the body's hormone system. Hormones regulate critical life functions, including growth, development, metabolism, and reproduction. When marine animals are exposed to these leaching chemicals, it can lead to developmental deformities in offspring, feminization of male fish, and a decreased ability to reproduce. This chemical threat compounds the physical dangers of plastic, creating a complex and deadly challenge for marine organisms at every stage of life.

Ecosystem-Level Disruption and Habitat Destruction

The impact of plastic pollution extends beyond individual animals to the very structure and function of entire marine ecosystems. The accumulation of plastic debris can physically alter habitats, fundamentally changing the living conditions for the organisms that depend on them. These large-scale changes can have cascading effects, disrupting the delicate balance that sustains a healthy marine environment.

On the seafloor, dense accumulations of plastic can smother benthic communities, cutting off the supply of oxygen and light to the sediment. This creates anoxic (oxygen-depleted) dead zones where few organisms can survive. In vital, light-dependent habitats like coral reefs and seagrass meadows, the impact is particularly severe. Plastic bags, wrappers, and other debris can settle on corals, blocking the sunlight needed by their symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae) to photosynthesize. This can cause coral bleaching and disease, turning vibrant, biodiverse reefs into barren graveyards. A 2018 study published in Science found that the likelihood of disease in corals increases from 4% to a staggering 89% when they come into contact with plastic.

Furthermore, floating plastic debris acts as a new and highly effective transport mechanism for organisms, a phenomenon known as "rafting." Algae, barnacles, and microbes can attach themselves to a piece of plastic and travel thousands of miles across oceans, far beyond their natural range. When these plastic rafts arrive in new locations, they can introduce non-native and potentially invasive species. These invaders can outcompete local organisms for resources, introduce new diseases, and disrupt the established ecological order, with unpredictable and often negative consequences.

—

Table: Common Plastic Types and Their Marine Impact

| Plastic Type | Common Sources | Est. Decomposition Time | Specific Marine Life Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) | Water bottles, food jars | 450+ years | Sea turtles, fish (ingestion of fragments) |

| High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) | Milk jugs, bottle caps, shopping bags | 100-500 years | Seabirds (ingest caps), turtles (ingest bags) |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | Pipes, packaging film | Indefinite | Releases toxic chemicals (e.g., phthalates) affecting all life |

| Polypropylene (PP) | Containers, fishing gear, ropes | 20-30 years | Whales, seals, dolphins (entanglement in ropes/nets) |

| Polystyrene (PS) | Foam cups, take-out containers | 50+ years (breaks into tiny beads) | Fish, invertebrates (ingestion of small particles) |

| Nylon | Fishing nets, ropes, clothing | 30-40 years | Ghost fishing: Kills fish, sharks, seals, turtles indiscriminately |

—

The Ripple Effect: Socio-Economic and Human Health Consequences

The devastating effects of plastic pollution on marine life do not occur in a vacuum. They create a powerful ripple effect that directly impacts human societies, economies, and even our own health. The degradation of marine ecosystems threatens the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people who depend on the ocean for food and income. This makes the fight against plastic pollution not just an environmental issue, but a critical matter of social and economic justice.

Coastal communities, particularly in developing nations, rely heavily on fishing for both sustenance and commerce. As plastic pollution leads to the death of fish, the destruction of critical nursery habitats like coral reefs, and the contamination of the food web, fish stocks decline. This directly threatens the food security and economic stability of these communities. Fishermen find more plastic than fish in their nets, and the fish they do catch may be smaller, less healthy, and contaminated with microplastics and their associated toxins. The aquaculture industry also suffers, as farmed fish are often raised in coastal waters tainted by plastic pollution.

The tourism industry, another economic cornerstone for many coastal regions, is also at risk. Beaches littered with plastic waste are a major deterrent for tourists. The image of a beautiful tropical paradise is shattered by the sight of plastic bottles, bags, and Styrofoam containers washed up on the shore. This "plastic tide" can lead to a significant loss of tourism revenue, impacting hotels, restaurants, and local businesses that depend on a healthy and pristine marine environment to attract visitors. The cost of cleaning up beaches and coastal areas is also a significant and growing financial burden for local governments.

Finally, the crisis is coming full circle to human health. As we consume seafood that has ingested microplastics, we are likely ingesting those same plastic particles and the toxins they carry. While the full extent of the impact on human health is still a topic of active research, initial studies are concerning. Scientists have confirmed the presence of microplastics in human blood, lungs, and placentas. The potential long-term health effects of this exposure—related to the toxic chemicals that plastics carry—are unknown but are a source of growing concern within the medical and scientific communities.

Conclusion

The effects of plastic pollution on marine life are profound, multifaceted, and unequivocally devastating. From the physical agony of entanglement and ingestion to the invisible poisoning of the food web by microplastics and their toxic hitchhikers, our plastic waste is waging a war on ocean ecosystems. It smothers vital habitats like coral reefs, transports invasive species across the globe, and ultimately threatens the very foundation of marine biodiversity. This is not a distant problem; it is a global crisis with direct consequences for human economic stability, food security, and health.

Confronting this challenge requires a monumental and coordinated effort. Bold action is needed from governments to implement robust waste management policies and from corporations to redesign products and take responsibility for their entire lifecycle. As individuals, our choices matter. We must consciously reduce our consumption of single-use plastics, advocate for change, support organizations working on the front lines, and participate in efforts to clean our coastlines and waterways. The health of our oceans is inextricably linked to the health of our planet and ourselves. Protecting marine life from the plague of plastic is not a choice; it is a shared responsibility and an urgent necessity.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What exactly are microplastics?

A: Microplastics are tiny plastic particles less than five millimeters (0.2 inches) in diameter. They come from two main sources. Primary microplastics are intentionally manufactured small, like microbeads in cosmetics or plastic pellets (nurdles) used in industrial manufacturing. Secondary microplastics are formed from the breakdown of larger plastic items, like water bottles, bags, and fishing nets, due to sun exposure, wind, and wave action.

Q: Which marine animals are most affected by plastic pollution?

A: Virtually all marine life is affected, but some groups are particularly vulnerable. Sea turtles are highly susceptible to both ingestion (mistaking bags for jellyfish) and entanglement. Seabirds, especially species like the Laysan albatross, ingest vast amounts of plastic, which they then feed to their chicks. Marine mammals like seals, sea lions, and whales frequently become entangled in "ghost" fishing gear. Filter feeders, from massive whale sharks to tiny mussels, are also heavily impacted as they inadvertently consume microplastics while feeding.

Q: What can I do as an individual to help reduce ocean plastic?

A: Individual actions, when multiplied, can create significant change. Key steps include:

- Reduce: Drastically cut down on single-use plastics like bags, bottles, straws, and cutlery. Opt for reusable alternatives.

- Reuse: Find new purposes for plastic items you already have instead of throwing them away.

- Recycle: Properly sort and recycle the plastics you cannot avoid, according to your local guidelines.

- Participate: Join local beach or river cleanups to remove plastic directly from the environment.

- Advocate: Support businesses that use sustainable packaging and encourage your local representatives to pass stronger policies regulating plastic production and waste.

Q: Does all plastic in the ocean float?

A: No, and this is a common misconception that complicates the problem. While some types of plastic, like polyethylene and polypropylene, are less dense than seawater and will float, others are denser and sink. Approximately 70% of the plastic that enters the ocean sinks to the seafloor. This means that the "garbage patches" we see on the surface represent only a fraction of the total problem. The plastic on the seafloor smothers marine life, pollutes deep-sea ecosystems, and is incredibly difficult to monitor and remove.

—

Article Summary

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of The Devastating Effects of Ocean Plastic on Marine Life. It begins by outlining the massive scale of the plastic pollution crisis, detailing how millions of tons of persistent plastic enter the oceans annually, fragment, and accumulate in global ecosystems. The core of the article explores the multi-pronged threats to wildlife, starting with direct physical harms like entanglement in ghost nets and ingestion of plastic mistaken for food, which cause injury, starvation, and death.

The discussion then moves to the insidious danger of microplastics, explaining how these tiny particles absorb toxins and poison the food web through bioaccumulation and biomagnification, leading to reproductive failure and disease in top predators. The article also examines ecosystem-level disruption, where plastic smothers critical habitats like coral reefs and transports invasive species. Finally, it connects the marine crisis back to humanity, highlighting the negative socio-economic impacts on fisheries and tourism, and the emerging concerns for human health from consuming contaminated seafood. The piece concludes with a powerful call to action, emphasizing the shared responsibility of governments, corporations, and individuals to address this urgent global threat.